Introduction and summary

From the earliest days of his presidential campaign, a constant refrain from Donald Trump has been the need to protect the United States from foreign threats, particularly violent crime that he falsely asserts is committed at high rates by immigrants to this country. The Trump administration’s protectionist, isolationist, nativist, and racist immigration policy is founded on the scurrilous notion that the United States needs to close the borders and restrict immigration to the country as a way to protect against the entry of violent crime. However, often overlooked in this debate is the degree to which exportation of violence goes in the other direction—that is to say, from the United States to other countries—and, in particular, the substantial U.S. role in providing guns that are used in lethal violence in other nations.

From 2014 to 2016, across 15 countries in North America, Central America, and the Caribbean, 50,133 guns that originated in the United States were recovered as part of criminal investigations.1 Put another way, during this span, U.S.-sourced guns were used to commit crimes in nearby countries approximately once every 31 minutes.2

Certainly, many of these U.S.-sourced crime guns were legally exported and were not diverted for criminal use until they crossed the border. The United States is a major manufacturer and a leading exporter of firearms, legally exporting an average of 298,000 guns each year.3 However, many of the same gaps and weaknesses in U.S. gun laws that contribute to illegal gun trafficking domestically likewise contribute to the illegal trafficking of guns from the United States to nearby nations.

This report discusses the scope of the problem of U.S. guns being trafficked abroad and used in the commission of violent crimes in other nations. For example, in 2015, a trafficking ring bought more than 100 guns via straw purchases in the Rio Grande Valley of the United States and smuggled them to Mexico. At least 14 of these firearms were recovered in Mexico.4

In addition, this report identifies a number of policy solutions that would help to reduce the flow of crime guns abroad and begin to minimize the U.S. role in arming lethal violence in nearby countries. These recommendations include:

- Instituting universal background checks for gun purchases

- Making gun trafficking and straw purchasing federal crimes

- Requiring the reporting of multiple sales of long guns

- Increasing access to international gun trafficking data

- Rejecting efforts that weaken firearm export oversight

The United States has a moral obligation to mitigate its role in arming lethal violence abroad. While there are many factors unique to each nation that affect rates of violent crime, there is more the United States could do to reduce the risks posed by U.S.-sourced guns that cross the border and are used in crime in nearby countries.

The U.S. is a primary source for crime guns in North and Central America as well as the Caribbean

The most obvious place to start when considering the impact of U.S.-sourced guns on other nations is to look at the immediate neighbors. Much has been written on the impact of U.S. guns arming the perpetrators of violent crime in Mexico. Organized criminal groups in Mexico use firearms to wage brutal wars against rival criminal groups and government agencies as well as to extort the civilian population. Many of the guns used by these criminal groups originate in the United States.5 According to data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), of the 106,001 guns recovered by law enforcement as part of a criminal investigation in Mexico from 2011 to 2016 and submitted for tracing, 70 percent were originally purchased from a licensed gun dealer in the United States.6 These U.S.-linked guns likely represent only a fraction of the total number of guns that cross the southern border, as they only account for those guns that were both recovered by law enforcement during a criminal investigation and submitted to ATF for tracing.7 Other estimates suggest that close to 213,000 firearms are smuggled across the U.S.-Mexico border each year.8 According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), nearly half of the U.S.-sourced guns recovered in Mexico are long guns, which include high-caliber semi-automatic rifles, such as AK and AR variants.9 This is a concern for Mexican law enforcement officials, who have reported that assault rifles have become the weapons of choice for Mexican drug trafficking organizations, in part because they can easily be converted into fully automatic rifles.10 The GAO also reports that, from 2009 to 2014, the majority of the crime guns recovered in Mexico that were originally purchased in the United States came from three southern border states: 41 percent from Texas, 19 percent from California, and 15 percent from Arizona.11

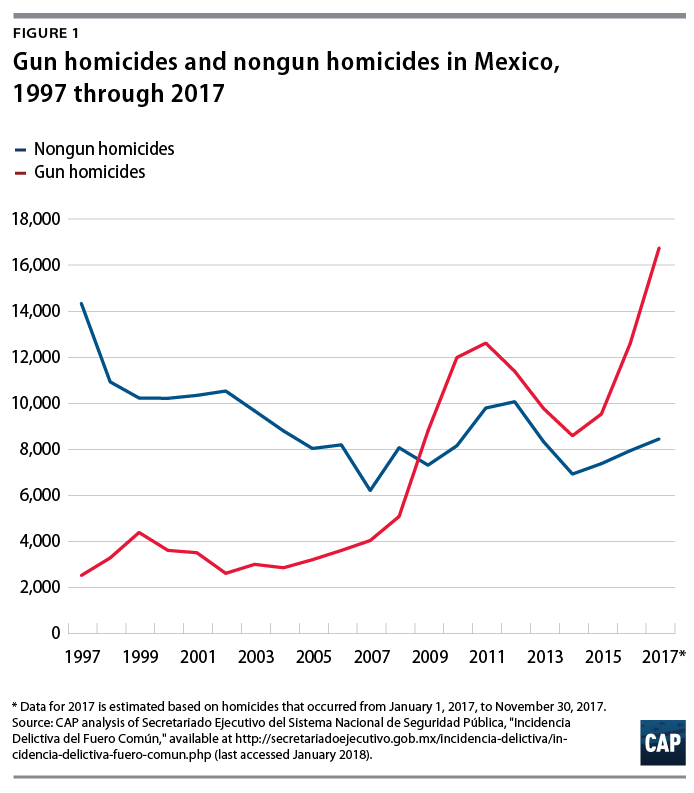

The impact of rampant gun trafficking from the United States to Mexico has been devastating. In 2017, Mexico reached its highest level of homicides in the past 20 years, with a rate of 20.5 homicides per every 100,000 people.12 While this figure is partly driven by high levels of impunity for criminal behavior,13 access to firearms has also been a key driver of the increase in homicides. In 1997, 15 percent of Mexico’s homicides were committed with a gun, yet, in 2017, that percentage rose to roughly 66 percent.14 The use of firearms during violent robberies has also increased. In 2005, 58 percent of robberies were committed with guns; in 2017, this figure increased to 68 percent.15

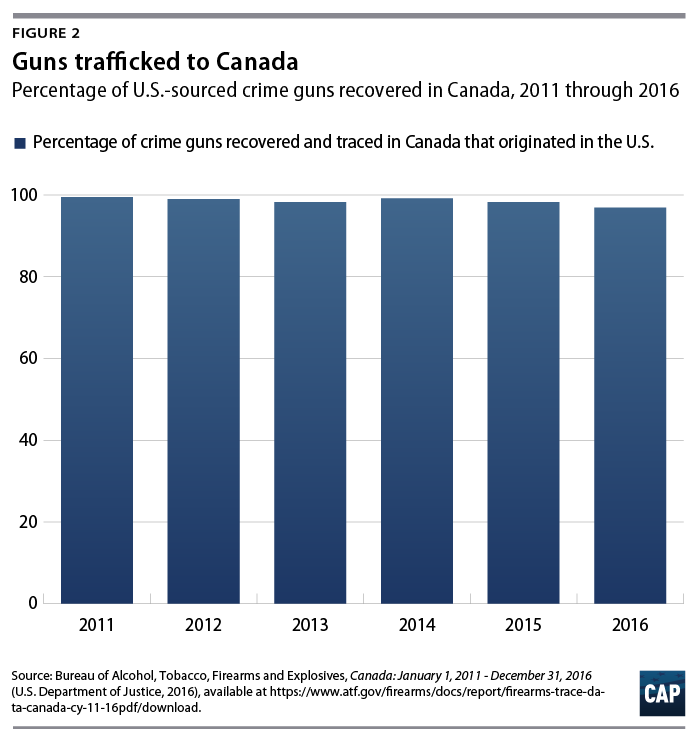

International gun trafficking is not limited to the U.S. southern border; guns are also trafficked out of the United States across the northern border into Canada. According to ATF data, of the nearly 8,700 guns recovered as part of a criminal investigation in Canada and submitted to ATF for tracing from 2011 to 2016, 98.5 percent originated in the United States.16 U.S.-sourced crime guns recovered in Canada come from a number of states, including the border states of Michigan and Vermont as well as states along the I-75 corridor that runs from Florida to Michigan.17

While Canada experiences much lower violent crime rates than Mexico and dramatically fewer gun-related homicides than the United States, Canadian law enforcement has nonetheless become concerned about the increasing use of semi-automatic rifles and handguns in gang-related crime in its cities.18 An Ottawa police inspector recently explained: “Ten years ago, 20 years ago … there wasn’t necessarily guns associated with street-level trafficking. There was violence but it wasn’t gun violence. Now you’re seeing more guns being used for enforcement or for intimidation, debt collection or protection.”19 The Canada Border Services Agency has noted an increase in illegal gun seizures at the border—up from 226 guns in 2012 to 316 guns in 2015.20

U.S. guns are also fueling lethal violence in Central America. A number of countries in Central American have been devastated by violence and, despite a recent reduction in homicides, Central America’s “Northern Triangle”—the region formed by El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—remains one of the most violent regions in the world.21 Much of this violence stems from gang-related drug trafficking, which, coupled with corrupt government institutions, income inequality, impunity for wrongdoers, and a recent history of violent conflict, has destabilized the entire region.22

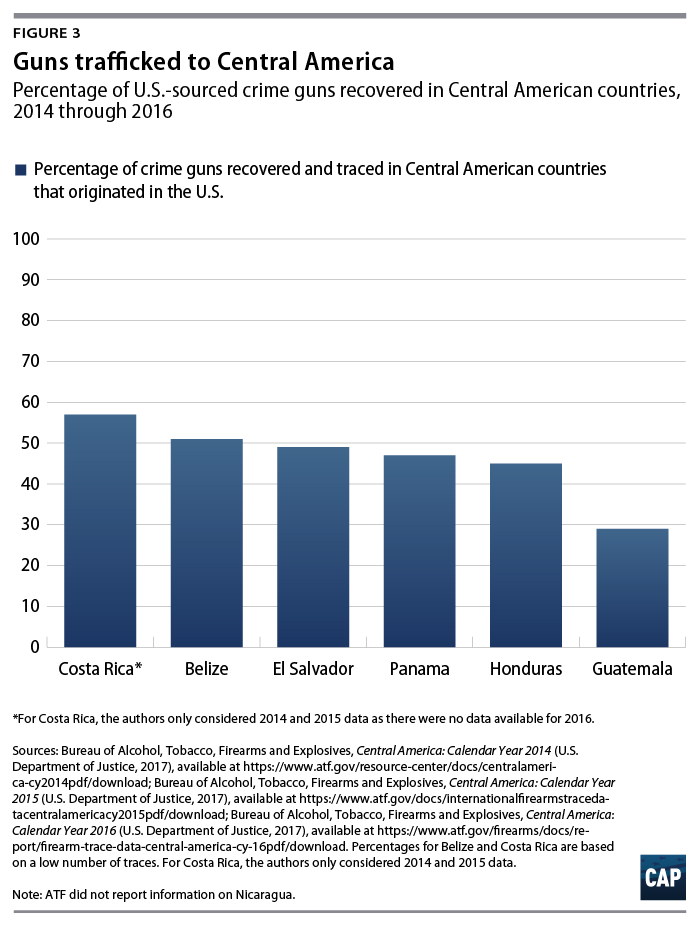

While many factors have contributed to violence in these countries, guns have played an outsized role in escalating the levels of lethality.23 And as with Canada and Mexico, many of these guns originate in the United States. From 2014 to 2016—the only years for which ATF has made this data publicly available—49 percent of crime guns recovered in El Salvador were originally purchased in the United States.24 Similarly, 45 percent of crime guns recovered in Honduras and 29 percent of those recovered in Guatemala have U.S. origins.25

Other Central American countries are also receiving U.S.-sourced guns used in crime. From 2014 to 2015, 57 percent of crime guns recovered and traced in Costa Rica originated in the United States, and from 2014 to 2016, 51 percent of such guns in Belize and 47 percent in Panama came from the United States.26

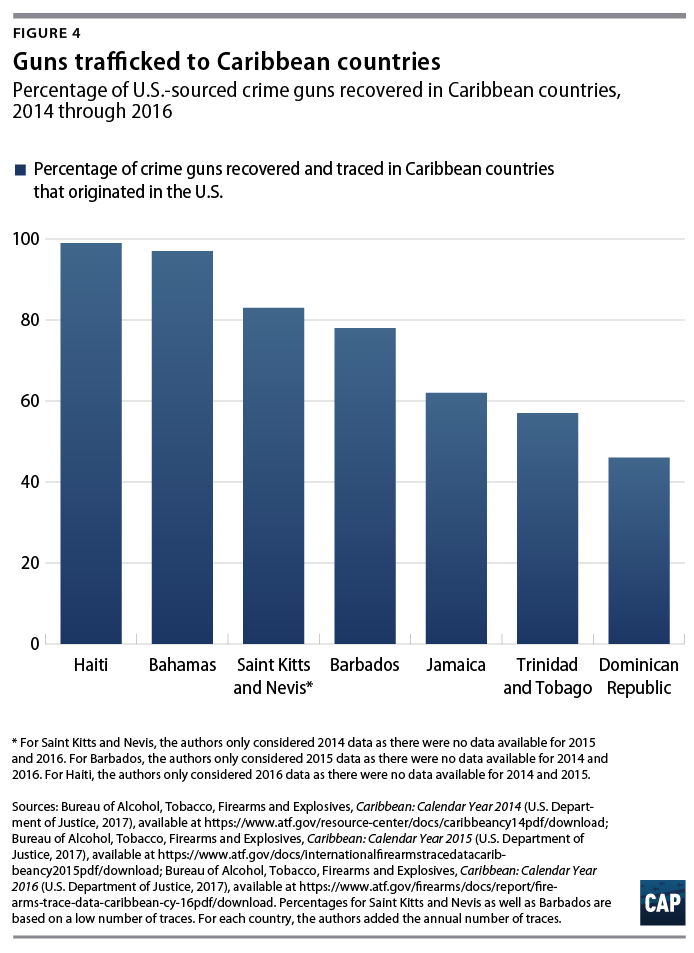

A significant number of U.S.-sourced guns have also been recovered during criminal investigations in the Caribbean. From 2014 to 2016, 97 percent of crime guns recovered in the Bahamas and submitted to ATF for tracing were first sold in the United States.27 During this same period, 62 percent of crime guns recovered in Jamaica originated in the United States, 57 percent in Trinidad and Tobago, and 46 percent in the Dominican Republic.28 Only one year of data is available for other Caribbean countries, but again, these data show high numbers of U.S.-sourced guns used in crime. In 2016, 99 percent of crime guns recovered in Haiti originated in the United States; in 2015, 78 percent of crime guns recovered and traced in Barbados came from the United States; and in 2014, 83 percent of crime guns recovered in Saint Kitts and Nevis had a U.S. origin.29

From 2014 to 2016, 50,133 guns that originated in the United States were recovered as part of criminal investigations in these 15 North American, Central American, and Caribbean countries,30 many of which receive more crime guns with origins in the United States than some U.S. states. For example, from 2014 to 2016, more than 33,000 U.S.-sourced guns were recovered in criminal investigations in Mexico. That exceeds the number of crime guns recovered and traced to a U.S. source in every U.S. state during the same period—except for California, Florida, and Texas.31 Similarly, from 2014 to 2016, both Canada and El Salvador recovered more U.S.-sourced crime guns than 20 U.S. states. 32

Weak laws and high rates of gun manufacture and import contribute to trafficking

What is a straw purchase?

A straw purchase occurs when an individual buys a gun on behalf of or at the request of a third person, often a person who is prohibited from buying guns. The straw purchaser fills out the required paperwork when the gun is sold from a gun dealer, falsely indicating on the form that he or she is the “actual buyer” of the gun. Following the sale at the dealer, the straw purchaser transfers the gun to the third party who was, in fact, the real intended recipient of the gun. Straw purchases are commonly used in gun trafficking schemes.33

The large inventory of guns in the United States—from both domestic manufacture and import—and the nation’s comparatively weak gun laws are key contributors to the flow of guns across the U.S. border and into nearby countries. Gun traffickers take advantage of both to purchase firearms in the United States at a relatively low cost before trafficking these weapons to nearby countries for resale at a substantial profit, creating a significant risk to these countries’ public safety in the process.34

While is it difficult to assess the precise number of guns in the United States, the best estimates suggest that there are roughly 300 million guns in circulation in this country.35 Moreover, in recent years, gun manufacturing in the United States has increased. While the United States manufactured an annual average of 3.5 million firearms from 1996 to 2005, it manufactured an annual average of 6.7 million firearms from 2006 to 2015.36 There is also a substantial number of guns imported into the United States; firearm imports have increased from an annual average of 1.3 million firearms from 1996 to 2005 to an annual average of 3.5 million firearms from 2006 to 2015.37 During the 10-year period from 2006 to 2015, a total of 67.5 million guns were manufactured in the United States and another 35.4 million guns were imported into the country.38

In addition to the substantial size of its gun market, the United States also has comparatively weaker gun laws than its regional neighbors. In Canada, for example, citizens have no constitutional right to possess firearms and most semi-automatic weapons are prohibited.39 Moreover, Canadian gun owners must obtain a license prior to purchasing a gun, undergo a background check, receive training, and be at least 18 years old.40 Furthermore, there is a mandatory 28-day waiting period for first-time owners.41

In Mexico, only the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA) can manufacture and sell guns, and any individuals who purchase a firearm must register the weapon with the ministry.42 In order to purchase a firearm, individuals must provide a letter of employment, a letter demonstrating that they do not have a criminal record, a copy of their military service card, proof of residency, photo identification, a copy of their birth certificate, and their Unique Population Registry Code (CURP).43 Finally, certain types of firearms are exclusively limited to military use, such as AR-15 and AK-47-style assault rifles.44

However, the strong gun laws in Canada and Mexico are undermined by their proximity to the United States and its comparatively weak laws. Traffickers along both the northern and southern U.S. borders have developed a variety of methods to exploit the United States’ weak gun laws in order to illegally traffic guns across the border into Canada and Mexico, where they can be sold at a considerable profit.

For example, from March to November 2016, a group of traffickers conspired to buy 36 guns through straw purchases from gun stores in Texas and smuggle them across the Mexican border.45 Along the northern border, in 2016, a man purchased 24 guns from a gun show using a straw purchaser on behalf of two other individuals who picked out the guns and provided cash for the purchase. At least one of these guns was recovered at a crime scene in Canada.46 Another brazenly illegal trafficking scheme involved individuals purchasing 100 handguns in the United States and leaving them at a library in Vermont near the northern border, where they were retrieved and smuggled to Canada.47

Recommendations

Many of the same policy recommendations often discussed to reduce gun trafficking within the United States would likewise have an impact on reducing trafficking across international borders. Additionally, there are measures that would help law enforcement efforts to combat international gun trafficking and shut off the illegal pipelines that send guns across the borders.

Institute universal background checks

Much has been written about the dangerous loophole in federal law that allows guns to be sold in private transactions without a background check and with no questions asked.48 While licensed gun dealers are required to conduct background checks before completing a sale, under federal law, individuals who are not dealers are free to sell guns without a background check. This gap in the law allows individuals who are prohibited from gun possession to easily evade that prohibition and buy an unlimited number of guns through private, under-the-table transactions.

To date, 19 states and Washington, D.C., have acted to close this loophole and now require background checks for all handgun sales.49 While it is difficult to establish a direct causal effect, academic research finds that these states have notably lower rates of gun trafficking. A 2009 study used crime gun trace data from ATF to explore the link between state gun laws and the rate of crime gun exports across states. The authors found a significant link between the regulation of private gun sales and lower rate of crime gun exports across states.50 Additionally, a 2010 analysis conducted by Mayors Against Illegal Guns found that states that do not require background checks for all handgun sales at gun shows have rates of crime gun exports that are more than 2.5 times greater than states that do.51

Similarly, closing this loophole and requiring a background check for all gun sales—even those between unlicensed individuals—would help to reduce illegal gun trafficking across the U.S. border. Recently, the percentage of U.S. firearms recovered in British Columbia—a Canadian province bordering Washington state—decreased significantly.52 Canada’s National Weapons Enforcement Support Team attributes this trend to the recently passed laws requiring background checks on all gun sales in Oregon and Washington state.53 Moreover, the GAO found that traffickers that send firearms to Mexico often use secondary markets such as gun shows—where private sellers often sell guns without a background check in states that have yet to close this loophole—to acquire and traffic firearms.54

Make gun trafficking and straw purchasing federal crimes

One of the key gaps in current law, which enables both domestic and international gun trafficking, is the absence of a federal law specifically targeting the criminal conduct involved in illegally trafficking guns. Under current law, individuals who knowingly facilitate illegal trafficking by transferring multiple guns to individuals prohibited from gun possession or through straw purchases are often only able to be prosecuted for a paperwork violation. The lack of a dedicated and specific federal criminal offense for gun trafficking and straw purchasing makes it difficult to focus enforcement efforts on those individuals responsible for creating sophisticated gun trafficking channels, which flood vulnerable communities on both sides of the border with guns.

A number of high-profile law enforcement organizations support strengthening the federal law with respect to gun trafficking and straw purchasing, including the Major Cities Chiefs Association and the International Association of Chiefs of Police.55 A number of bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress to address these gaps in the law, including the Gun Trafficking Prevention Act of 2017,56 the Stop Illegal Trafficking in Firearms Act of 2017,57 and the Countering Illegal Firearms Trafficking to Mexico Act,58 although none have moved in committee or received a hearing.59

Mandate the reporting of multiple sales of long guns

One of the tools that federal law enforcement agents use to identify potential gun trafficking are reports from gun dealers noting when an individual buys multiple firearms within a short period of time.60 Under current federal law, licensed gun dealers are required to report to ATF when someone buys more than two handguns in a five-day period.61 However, this statutory requirement does not apply to multiple sales of long guns, such as rifles and shotguns.

In 2011, ATF attempted to partially fill this reporting gap in order to address illegal gun trafficking to Mexico, using what is known as the agency’s demand letter authority to require gun dealers in the four southern border states—Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas—to similarly report to ATF when, within five business days, an individual buys two or more semi-automatic rifles that are capable of accepting a detachable magazine and are larger than .22 caliber.62 In light of Mexican drug trafficking organizations’ growing preference for high-powered assault rifles, this reporting requirement is particularly relevant in efforts to address international gun trafficking. However, each year, there are efforts to attach a new restrictive rider on ATF’s budget to prohibit the bureau from requiring this additional reporting in the four border states. Stand-alone legislation has recently been introduced in Congress to similarly restrict this reporting requirement.63 At a minimum, Congress should reject these efforts aimed at eliminating this important investigative resource for federal law enforcement, as it helps to address illegal gun trafficking. Additionally, Congress should act to amend the existing statutory requirement to require all gun dealers—not just those in the southern border states—to report multiple sales of long guns in the same manner that they currently report such sales of handguns, as proposed in the Multiple Firearm Sales Reporting Modernization Act of 2017.64

Increase access to data related to international gun trafficking

While ATF publishes annual reports containing aggregated data about U.S.-sourced guns recovered in criminal investigations abroad, they leave out crucial information that would help to inform public policy. More detailed information, such as the types and caliber of firearms recovered, as well as a breakdown of which states supplied the guns recovered in a particular country, would be useful for federal, state, and local policymakers seeking to reduce both domestic and international gun trafficking. ATF should make these data available as part of its annual reports.

Moreover, while ATF has begun publishing reports that provide data on the number of U.S.-sourced guns recovered in criminal investigations in the 15 countries discussed in this report, there is still a dearth of information about the flow of U.S. guns to other nations. For example, a recent study of more than 10,000 firearms seized by the Federal Police of Brazil, found that around 1,500 of these guns originated in the United States, making the U.S. the largest foreign source of illegal firearms in Brazil.65 ATF should increase international gun tracing efforts and publish information about crime guns recovered in other parts of the world, such as South American countries like Brazil and Colombia. These countries present homicide rates of more than 25 per every 100,000 people and are among the most violent nations in South America.66

Reject efforts to weaken oversight of firearm exports

One proposal currently under consideration by the Trump administration would shift the responsibility of reviewing and approving the exportation of small arms—handguns and many types of long guns, including assault-style rifles—from the U.S. State Department to the Commerce Department.67 This proposal has raised a number of concerns among national security and human rights experts, who caution that such a move could weaken oversight of these transactions and potentially open up the possibility of these exported firearms being diverted into the hands of criminal and terrorist organizations abroad.68 In September 2017, Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD), Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, expressing concerns about the proposal. In their letter, the senators highlighted the risks posed when small arms end up in the wrong hands: “As you are aware, combat firearms and ammunition are uniquely lethal; they are easily spread and easily modified, and are the primary means of injury, death, and destruction in civil and military conflicts throughout the world. As such, they should be subject to more – not less – rigorous export controls and oversight.”69

In light of the high number of U.S.-sourced guns recovered in connection with violent crime abroad, the current administration should consider options for strengthening oversight of firearm exports rather than weakening such oversight through a transfer of this responsibility to the Commerce Department.

Conclusion

Much of the discussion about gun violence in the United States focuses almost exclusively on the scope and scale of gun violence in this country; the impact on U.S. communities; and policy or programmatic solutions to address it. However, this conversation often fails to consider how the confluence of high levels of gun manufacturing and gun ownership in the United States, coupled with the numerous gaps and weaknesses in U.S. gun laws, results in the exportation of lethal violence to other countries. Policymakers in the United States have a moral obligation to take action to strengthen gun laws in an effort to improve public safety inside and outside of U.S. borders.

About the authors

Chelsea Parsons is the vice president of Guns and Crime Policy at American Progress. Her work focuses on advocating for progressive laws and policies relating to gun violence prevention and the criminal justice system at the federal, state, and local levels. In this role, she has helped develop measures to strengthen gun laws and reduce gun violence that have been included in federal and state legislation and executive actions. Prior to joining the Center, Parsons was general counsel to the New York City criminal justice coordinator, a role in which she helped develop and implement criminal justice initiatives and legislation in areas including human trafficking, sexual assault, family violence, firearms, identity theft, indigent defense, and justice system improvements. She previously served as an assistant New York state attorney general and a staff attorney clerk for the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Eugenio Weigend is the associate director for Guns and Crime Policy at American Progress. His work has focused on public security. He has conducted research on arms trafficking, organized crime and violence, firearm regulations in the United States, and the illegal flow of weapons into Mexico. He has a Ph.D from Tecnologico de Monterrey and a master’s degree in public affairs from Brown University.