See also: Poverty and Opportunity Profile: Millennials by Half in Ten and Generation Progress

Half in Ten and the Center for American Progress recently conducted a study of public attitudes toward federal anti-poverty efforts on the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. We closely examined the beliefs of younger Americans toward work, economic opportunity, and the social safety net. Our national survey of more than 2,000 adults included a significant oversample of Millennials ages 18 to 34, providing us with a total of 1,035 interviews with this important constituency and allowing us to compare their attitudes with older Americans. The full survey methodology is described below.

Overall, the study finds that Millennials are more likely than older Americans to face direct economic problems. Findings also indicate that they are more supportive than non-Millennials of past War on Poverty efforts, as well as new proposals to reduce poverty by focusing on jobs, wages, and educational opportunities. Although these differences are often matters of degree rather than differences of opinion between age groups, the data suggest that Millennials are likely to be very strong supporters of renewed efforts to fight poverty and expand economic opportunity by addressing the problems of a low-wage economy and reduced economic mobility.

Comparisons between Millennials and other Americans are described in detail in the full report. The most important findings from the oversample of Millennials include:

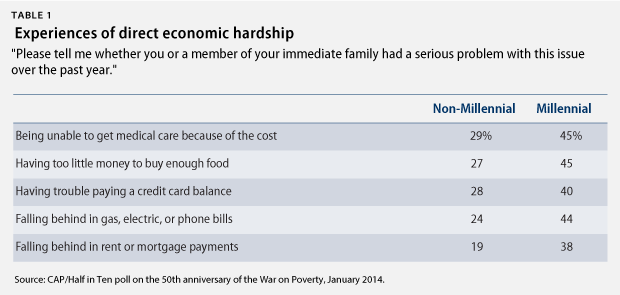

Millennials are much more likely than older Americans to report facing serious economic problems in the past year. Although non-Millennials are more likely than Millennials to say that their family incomes are falling behind the cost of living—67 percent versus 47 percent, respectively—this is really a matter of perspective as younger Americans report much higher levels of direct economic hardship for themselves and their families. As Table 1 highlights, Millennials are twice as likely as non-Millennials to report having had serious problems falling behind in rent or mortgage payments in the past year—38 percent versus 19 percent, respectively. More than 4 in 10 Millennials, compared to less than 3 in 10 non-Millennials, report serious problems affording medical care, not having enough money for food, paying utility bills, and paying credit card balances. And a majority of Millennials—53 percent—report that someone in their immediate family or a close relative is poor, basically equal to the findings among older Americans—54 percent.

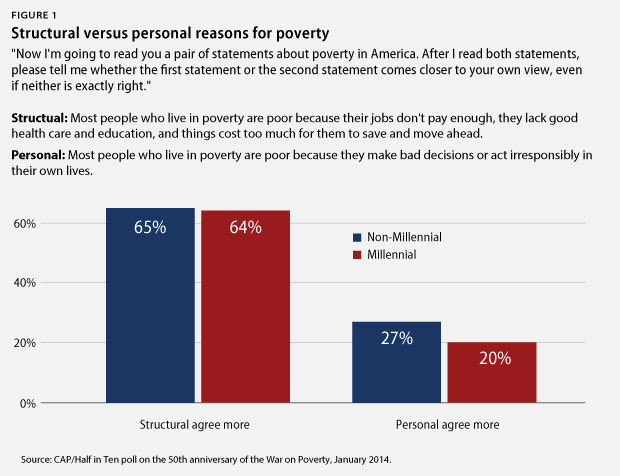

Millennials and older Americans are in basic agreement that structural economic problems are the primary cause of poverty rather than personal failings. Our study tested reactions to a series of attitudinal statements about poverty and the poor. As described in the longer report, many of the harshly negative attitudes about the poor that defined policy debates in the 1980s and 1990s appear to have receded given the realities of the contemporary economy. Strong majorities of Americans, younger and older alike, believe that:

- “Most people living in poverty are decent people who are working hard to make ends meet in a difficult economy” (82 percent of Millennials and 78 percent of non-Millennials agree)

- “The primary reason so many people are living in poverty today is that our economy is failing to produce enough jobs that pay decent wages” (78 percent of Millennials and 77 percent of non-Millennials agree)

- “Many people living in poverty are unfairly criticized by others as lazy or undeserving” (74 percent of Millennials and 65 percent of non-Millennials agree)

As the chart below shows, by a more than 2-to-1 margin, Americans across all ages identify structural economic reasons as the root cause of poverty rather than personal ones. In a forced choice test, 64 percent of Millennials and 65 percent of non-Millennials agree more with the statement, “Most people who live in poverty are poor because their jobs don’t pay enough, they lack good health care and education, and things cost too much for them to save and move ahead.” In contrast, only 27 percent of non-Millennials and 20 percent of Millennials agree more with the statement, “Most people who live in poverty are poor because they make bad decisions or act irresponsibly in their own lives.”

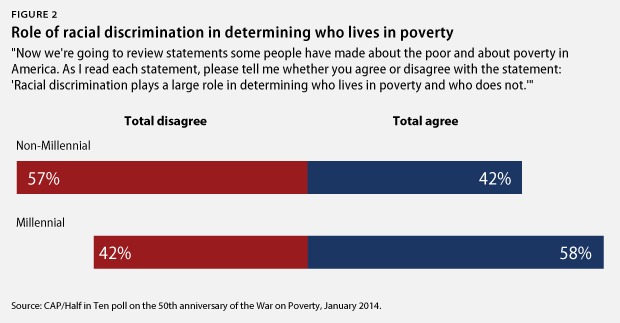

Millennials are much more likely than older Americans to believe that racial discrimination determines who ends up in poverty and who does not. While younger and older Americans are fairly aligned in their views about the economic causes of poverty, their opinions diverge sharply on matters of race. A sizeable majority of non-Millennials—57 percent—disagrees with the statement that “Racial discrimination plays a large role in determining who lives in poverty and who does not.” In contrast, a nearly identical proportion of Millennials—58 percent—believes that racial discrimination does play a large role in determining who ends up in poverty. The 16-percentage-point difference in agreement on this question was the largest gap registered between younger and older Americans in the entire survey.

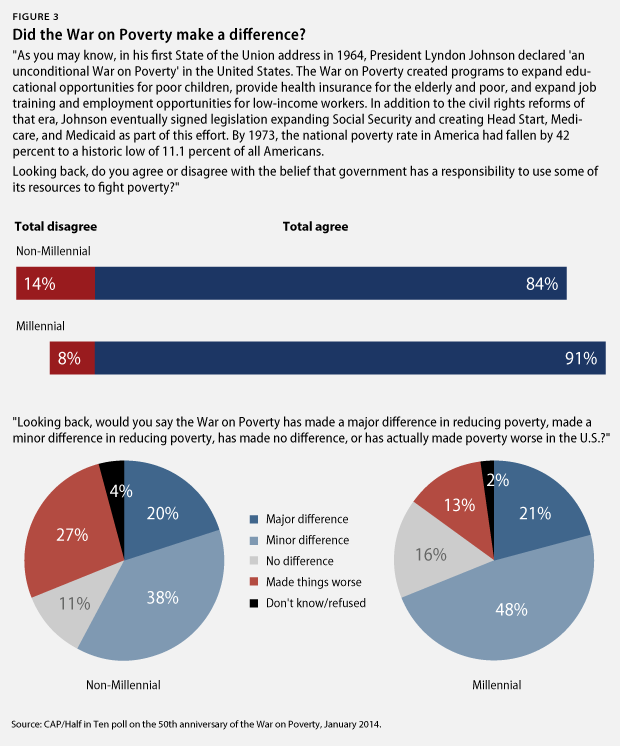

Millennials report more favorable attitudes toward the original War on Poverty than do older Americans. As our original report shows, Americans overall hold mixed retrospective views about the War on Poverty—43 percent of Americans overall rate the War on Poverty unfavorably; 22 percent rate it favorably; 20 percent rate it neutrally; and another 14 percent cannot identify it at all. But when presented with factual information about what the War on Poverty set out to do and what it accomplished, Americans overwhelmingly agree that the government has a responsibility to use some of its resources to fight poverty; more than 6 in 10 Americans believe that it has made a difference, albeit primarily a minor difference, in achieving its goals. Millennials, born well after the War on Poverty began and after conservative arguments against the federal government’s role in fighting poverty strengthened in the 1980s and 1990s, are surprisingly more supportive of its goals and accomplishments. Millennials report higher average favorability ratings for Head Start, Pell Grants, the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, and food stamps than their elder peers.

After hearing a factual description about President Johnson’s War on Poverty, a full 91 percent of Millennials say that looking back, the government has a responsibility to use its resources to help fight poverty—7 percentage points higher than non-Millennials. Nearly 7 in 10 Millennials—69 percent—compared to 58 percent of non-Millennials, also believe that the War on Poverty made a difference; 21 percent of Millennials say that it made a major difference and 48 percent say that it made a minor difference. Non-Millennials are twice as likely as Millennials to say that the War on Poverty actually made things worse—27 percent versus 13 percent, respectively.

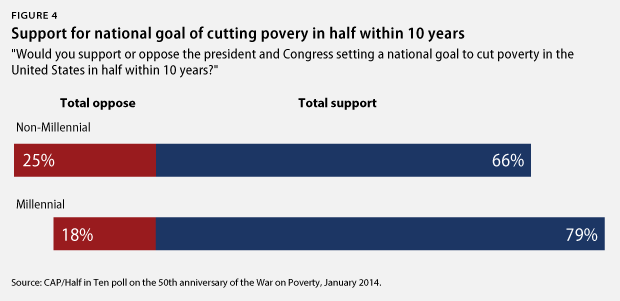

Millennials are among the strongest supporters of a targeted goal of cutting poverty in half within the next decade. Despite mixed reactions to the original War on Poverty efforts, 70 percent of Americans say that they would support the president and Congress in setting a goal of cutting poverty in half over the next 10 years. Nearly 80 percent of Millennials support this targeted poverty-reduction goal, compared to two-thirds of non-Millennials. Unlike older Americans, strong majorities of Millennials say that they would still support this goal even if it cost businesses more in terms of wages and benefits and required higher taxes on the wealthy and more government spending. Combining all three of these questions into one measure of support, 60 percent of Millennials would strongly support a new goal of cutting poverty in half even with the requirements on business and government, compared to 45 percent of non-Millennials.

In terms of priorities for addressing poverty, both Millennials and non-Millennials favor new efforts to create jobs and increase wages as their top priority—45 percent and 39 percent, respectively. But Millennials’ second-highest priority is college access and affordability—29 percent—while non-Millennials look toward new efforts on job training—33 percent.

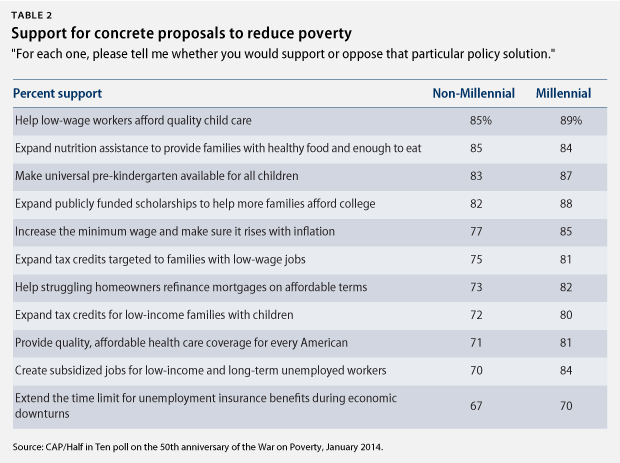

Millennials strongly support concrete proposals to reduce poverty and protect the more traditional social safety net. As the table below highlights, Millennials report higher levels of support than non-Millennials on 10 out of 11 proposals for reducing poverty. Support tops 80 percent among Millennials for every measure tested, with the exception of extending unemployment insurance—70 percent support. The highest levels of support among Millennials emerge for policies to help low-wage workers afford quality child care (89 percent support), expand publicly funded college scholarships (88 percent), and provide universal pre-kindergarten for all children (87 percent support). Millennials are also 6 to 14 percentage points more supportive than non-Millennials of expanding the EITC and Child Tax Credit, helping more people refinance mortgages, providing affordable health coverage to all Americans, and creating subsidized jobs for low-income and long-term unemployed workers.

The findings in this memo are based on a representative national survey of 1,000 adults via landline and cell phones conducted by GBA Strategies. In addition to the base sample of 1,000 adults, oversamples were conducted among three critical constituencies—African Americans (347 total respondents), Hispanics (370 total respondents), and Millennials ages 18 to 34 (1,035 total respondents) using landlines, cell phones, and online surveys. The survey was conducted November 12–26, 2013, among a total of 2,052 respondents.

Responses based on the full sample have a margin of error of +/- 2.2 percent at the 95 percent confidence level. Millennial results have a margin of error of +/- 3.1 percent.

John Halpin is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Karl Agne is a founding partner of GBA Strategies.